4 skills senior engineers often think they have but rarely do

The gap between engineering expertise and effective leadership.

Engineering Leadership

Most companies nowadays have evolved and have two distinct paths for engineers and managers.

I am pleased to see that to progress as an engineer you don’t need to become a manager. You can if you want to, but it’s not the only path. In fact, doing so is considered a transition.

It’s like being a Cloud Engineer and deciding to become a DevOps Engineer. Still working in tech, with a similar structure, both hard to describe to my parents 😅, and with different challenges.

So, much like this transition, becoming a manager is not a step up, it’s a lateral move.

Being a manager is not the only way to be an engineering leader. In the teams that I work with, I want everyone to be a leader! Each having a different level of influence but a leader nonetheless. Being a leader is not only championing technical skills but also behavioural ones.

For senior, staff, and principal engineers leadership typically means leading projects that span more than one team and being responsible for the technical aspect mostly. Their role is to make sure we make the right technical decisions to deliver efficiently.

For engineering managers, leadership typically means focusing more on the people, process, and delivery side of things. Simply put, EMs bring engineers together and work with other stakeholders to deliver value to the company, which requires making sure the people in the team learn new things, progress in their careers, and work cohesively together.

In this post, I highlight some management skills that senior engineers often think they have but rarely do, and most importantly, how to cultivate them.

Consider supporting my work and subscribing to this newsletter.

As a free subscriber, you get:

✉️ 1 post per week

🧑🎓 Access to the Engineering Manager Masterclass

As a paid subscriber, you get:

🔒 1 chapter each week from the book I am writing “The Engineering Manager’s Playbook”

🔒 50 Engineering Manager templates and playbooks (worth $79)

🔒 The complete archive

It’s more than just information transfer

The Assumption: “I’m clear when I communicate. My team knows what I want.”

The Reality: Clear communication isn't giving instructions, it's making sure understanding, alignment, and emotional buy-in.

Engineers are used to communicating in precise, and concise ways which is great. The assumption here is that if you explain things clearly, the team will follow along. But this is not always the case.

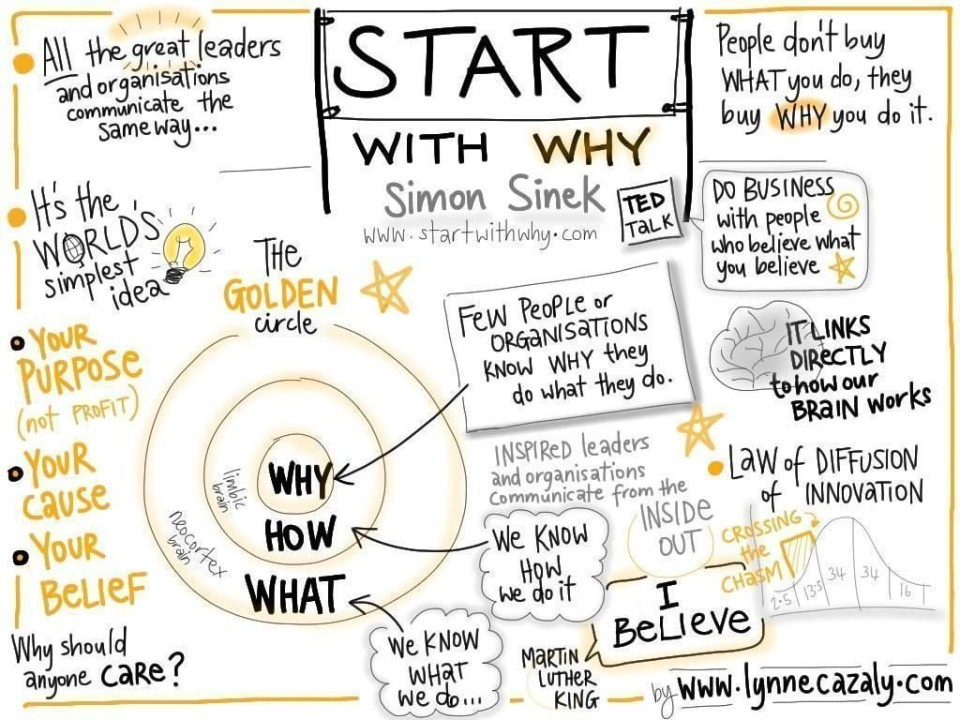

Communication requires a focus on both content and context. Whenever you need to communicate the “what” you need to also explain the “why”. Often multiple times, and in different ways.

Difficult times will come when you’ll need to prepare really well how you share a message.

Why do we need to work on this boring complex project? Why does it matter to the business? Why are we making a decision against popular opinion? Why is the company making certain roles redundant?

Providing the “why” does not guarantee buy-in from your team, but helps a lot with understanding and even when people disagree they can appreciate the context, and commit to it.

How to get better at communicating:

Zoom out: Whenever introducing a new project, a change, or difficult news, start with the broader context, before diving into the specifics.

Involve the team in the decision (when possible): After providing the context, constraints, or goals (the “what” and “why”) work with your team to formulate and plan the “how”. Avoid prescribing solutions, but rather present goals/opportunities.

Let go without losing control

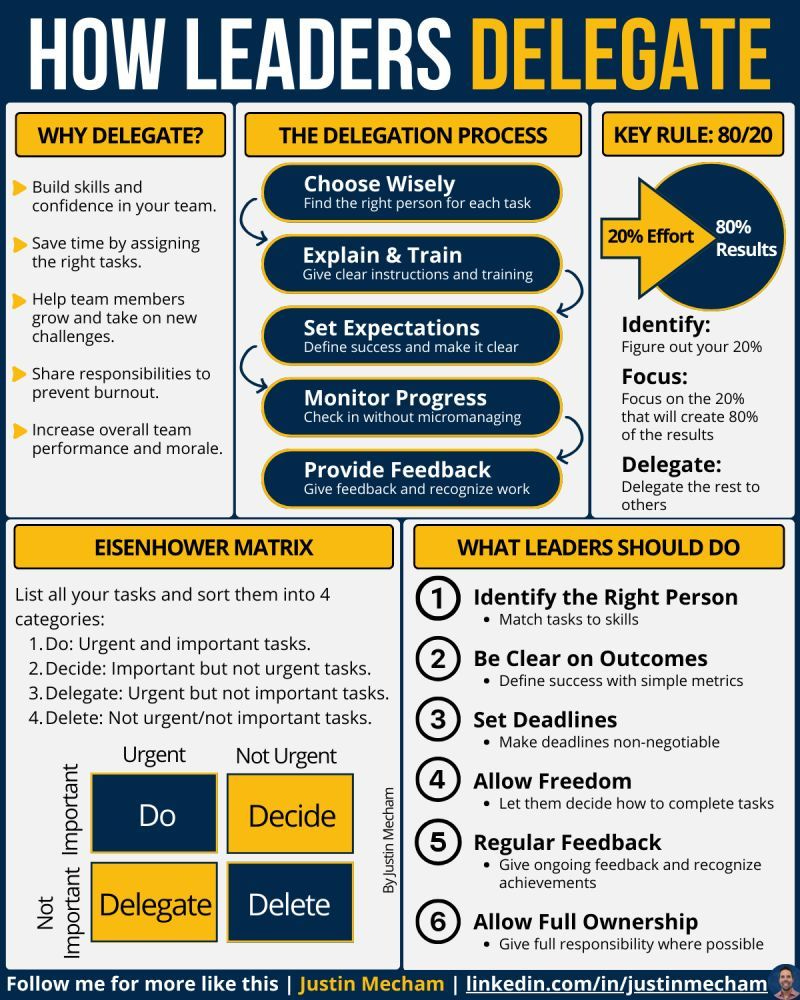

The Assumption: “I can delegate tasks. I know what my team can handle.”

The Reality: Delegation isn’t just offloading work, it’s cultivating trust, autonomy, and professional growth.

In a previous company, the manager (let’s call her Maria) before I joined had assigned a project to an engineer (let’s call him John).

Maria shared the “why”, and the “what” and John was very clear on what needed to be done and the timelines he needed to work within.

The project started, and Maria got very busy with other responsibilities, she detached from the project with the belief that it was in good hands and with the hope that John would raise with her any issues as they appeared.

That was the first time John was leading such a big project and got completely overwhelmed. He wanted to prove himself though as he was fairly new to the company and didn’t want to bother Maria with issues he was facing.

The result, as you can imagine was that the project got delayed and everyone was frustrated.

One would say that John should have communicated earlier with Maria and flagged issues as they arose. I agree with that, but what I also see in this situation is that Maria didn’t delegate successfully.

Managers sometimes feel like it will be considered micromanagement if they are still involved in projects that they delegate. How do we find the right balance here?

How to get better at delegating:

Start small: Gradually delegate more complex tasks. As your team members succeed, increase the level of difficulty.

Trust, but verify: Instead of micromanaging, set clear expectations and milestones. Regular check-ins help ensure progress without you hovering over their shoulder.

Provide autonomy: Give your engineers the freedom to approach tasks in their own way. It may not look exactly how you’d do it, but that’s okay as long as the results are there.

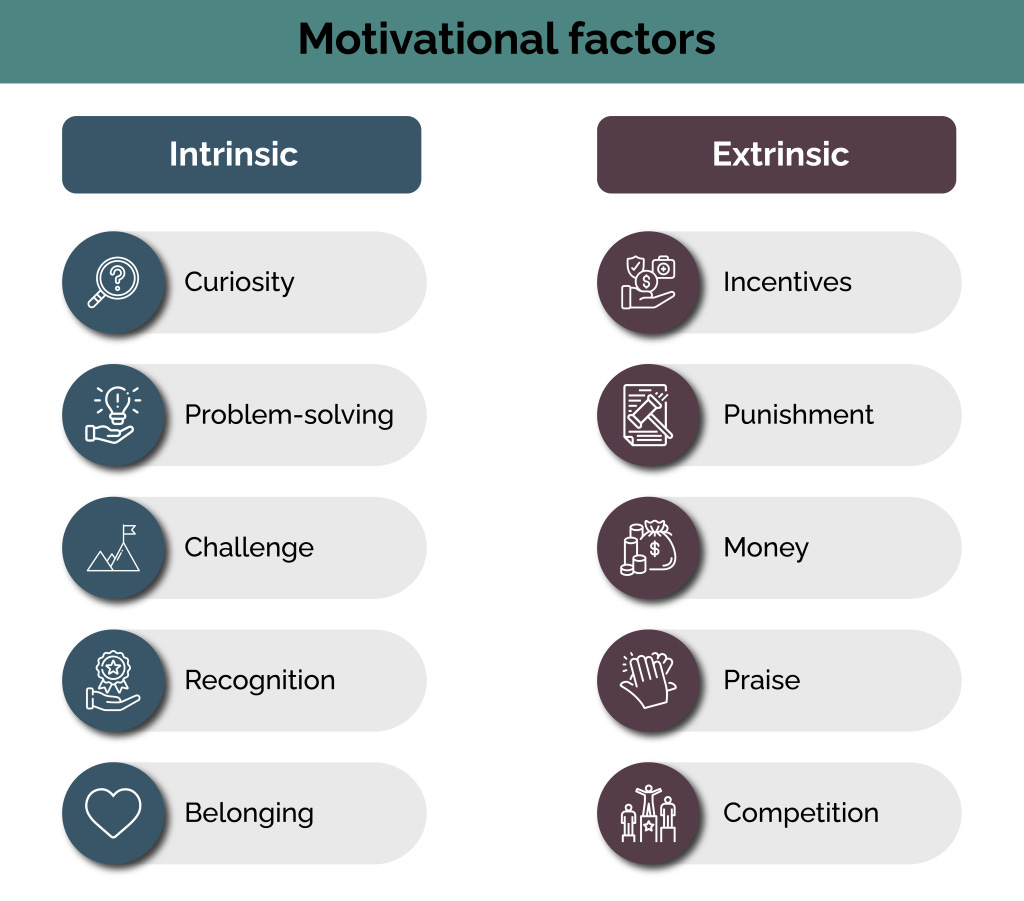

Understand what motivates people

The Assumption: “I know my team’s strengths and weaknesses. I don’t need to get too personal.”

The Reality: Management isn’t assessing technical abilities, it’s understanding and addressing the human element.

Some companies have a culture referred to as “up or out”. If you don’t get promoted within 2 years, you’re out. I don’t subscribe to it.

It’s perfectly fine (if not desirable) for engineers in my team to have different goals.

Some aim to become senior, while others may not care about titles and simply want to learn new technologies. Some are perfectly happy at their current level and prefer to stay there for the foreseeable future. Others might seek a higher salary, a transition into management, or even be willing to take a pay cut to switch to a new team.

The point I am trying to make here is that engineers have different goals and are motivated by different things. Growth does not look the same for everyone.

It’s through real and deep connection that you as a manager can deeply understand the people you are working with, what they’re motivated by, and the goals they have (regardless if they align with what you can provide or not at that company).

A principal engineer I used to manage wanted to become CTO. My company already had a CTO, and going for that specific role within the company was not an option we had.

Achieving his goal of becoming CTO would likely mean leaving the team and the company. However, that’s what we worked towards. That on its own created opportunities for other people in the team to elevate, and gave real motivation to everyone to be better, which brought great results in the long term.

How to get better at connecting with people:

Be present: Regularly check in with your team, not just on work progress, but on how they’re doing overall. Make space for 1:1 conversations that aren’t solely task-related. Never skip your 1:1s.

I hold a regular 1:1 with everyone reporting to me, and a monthly extended 1:1 which focuses only on individual goals set by my reports.

Listen actively: When someone shares a challenge, don’t just jump to fix it. Sometimes, people need to feel heard before solutions are offered.

Be vulnerable: Share your own struggles and experiences when appropriate. This builds trust and demonstrates that you understand their challenges firsthand.

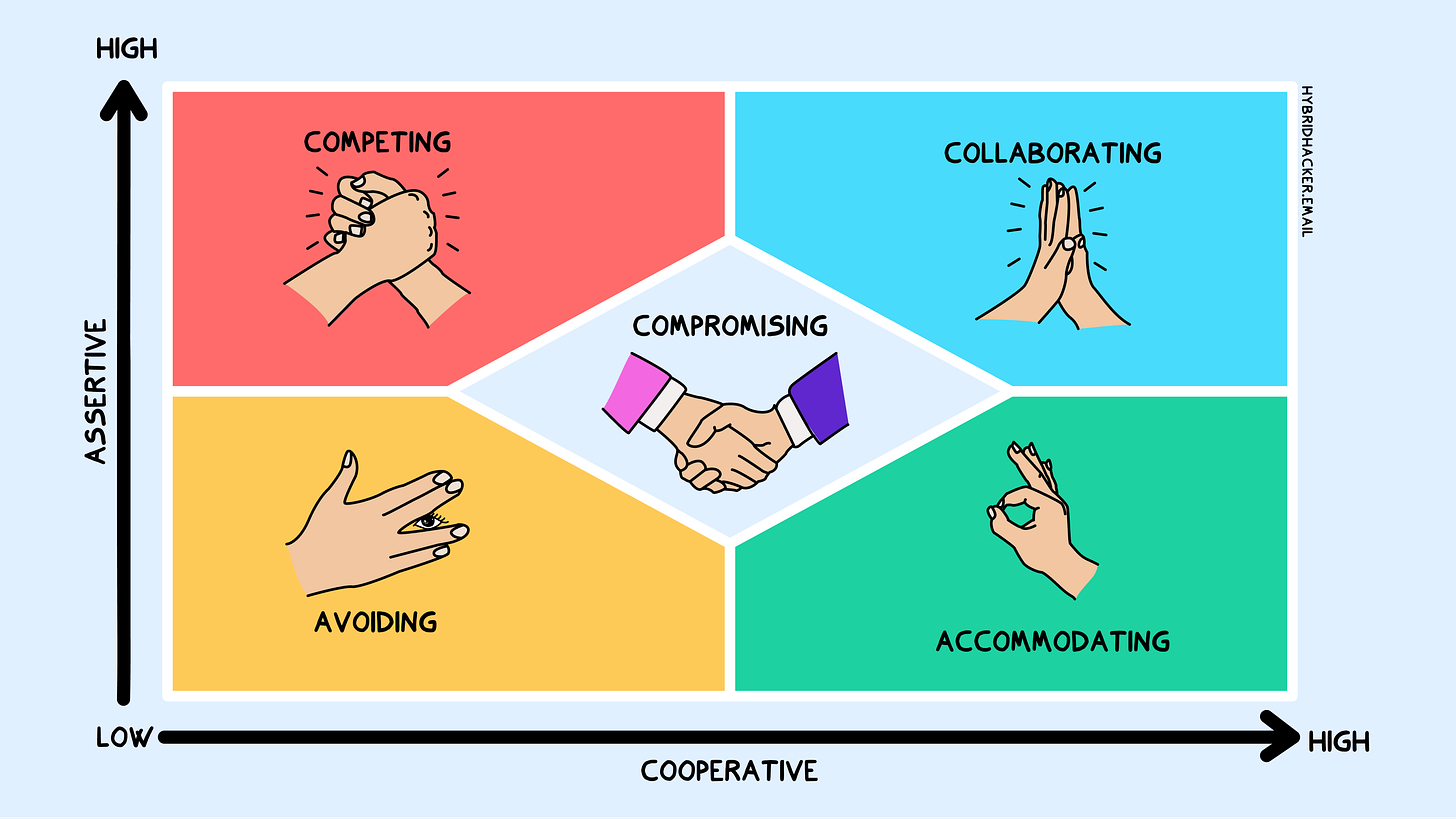

It’s more than keeping the peace

The Assumption: “I run a solid team. There won’t be conflicts if we’re all focused on the work.”

The Reality: Conflict is inevitable in any team, especially in high-pressure environments.

The best colleagues I’ve had were never my best friends. I have regular healthy conflicts with the people I care about.

I admire my manager, but I don’t agree with every decision he makes.

I love my partner, but we still have arguments (I am mostly right but let’s keep this just between us, Aggie I love you!).

The expectation that at work conflicts will not arise is a naive one. Especially when people care and are passionate about their work.

All sorts of ideas and suggestions will come from people and sometimes they will feel strongly about them.

If conflicts are not addressed promptly and as they happen, the possibility of holding grudges and creating a toxic environment over time becomes certain.

I feel like I am stating the obvious here, but resolving conflict is not everyone’s favourite activity. It’s stressful and uncomfortable.

How to get better at handling conflicts early:

Address issues early: Don’t wait for conflicts to escalate. Step in when you notice tension brewing and mediate a discussion before it gets out of hand.

Focus on solutions, not blame: Encourage a problem-solving mindset. When conflicts arise, guide the conversation towards finding common ground or compromise, rather than dwelling on mistakes.

Encourage open dialogue: Create an environment where team members feel safe to voice concerns and disagreements without fear of retribution.

TL;DR

Communication: Focus on clarity, but don’t forget the importance of context, storytelling, and ensuring understanding.

Delegate effectively: Trust your team with complex tasks and give them room to grow, while maintaining oversight.

Lead with empathy: Understand your team’s motivations and struggles, and make time for personal connection.

Handle conflicts early: Don’t avoid conflict; step in to resolve it before it impacts the team’s dynamics.

Useful links

👨💻 Become a better Software Engineer with CodeCrafters (use my partner link to get 40% off and build your own Redis, Git, Kafka and more from scratch).

🎯 Book a mock interview with me (System design or Behavioural & Leadership) to smash your next real interview!

👋 Let’s connect on LinkedIn!